Instafamous

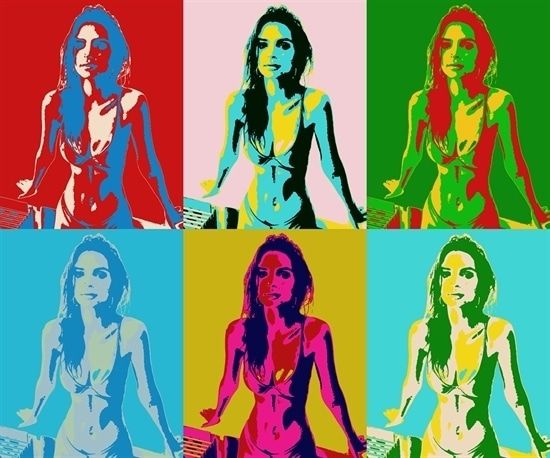

Warhol said, “In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes.” He was onto something. The nature of fame has changed a lot since then, because the nature of the media has changed. Warhol was working in an age of mass media—as is so well captured in his art. We now live in the age of democratized media and democratized media have democratized fame. The users of these democratized media, like Instagram, live partly in a virtual copy of the world. As in the work of Warhol, fame generates icons, and these icons take on a life of their own. In Dead Celebrities, Living Icons, cultural critic John David Ebert suggests that this is the very transformation Warhol anticipated:

Indeed, looking back over the various biographies of the celebrities we have covered in this book, it becomes clear that they represent the pioneers, as it were, of the current mass exodus into hyperreality in which every one of us, in the 21st century, is engaged … the creation of a virtual version of the self is part of the larger project of our technological construction of the world’s double … Andy Warhol, with his cult of the famous nobody, knew just what he was talking about and can be regarded as the prophet of where we’re at now.

On Instagram, users are pulled away from the real and toward the virtual or “hyperreal” by a confluence of factors. Our fascination with the virtual is not new, but increasingly pure fantasy exists alongside the everyday. New social phenomena like performative authenticity attempt to distinguish the real, and new dynamics in the content marketplace accelerate our construction of virtual identities in a sort of arms race.

The content on Instagram is like a limited map of life and the social world we inhabit, but it is an increasingly complete map becoming increasingly significant in real life. Although merely virtual, many are nonetheless drawn to escape into this virtual double of the world. “It is, in other words, an ersatz world—and also a meaningless one—into which the celebrity escapes by duplicating himself,” John David Ebert explains, “but one that is nonetheless the preferred mode of being. Everyone nowadays, in one form or another, wishes to escape into it.”

⁕ ⁕ ⁕

Influencers are the pioneers of an era in which one’s virtual presence becomes central to life in the real world. Influencers make their online persona their occupation, receiving endorsements from brands and promoting offshoot endeavors of their own. The line between virtual and real has recently become even blurrier—Heather Nolan reports that brands are now creating virtual influencers. A digital supermodel named Shudu Gram and a virtual influencer named Miquela now have hundreds of thousands of followers on Instagram—more than 2.4 million, in Miquela’s case. Their online presences are pretty convincing, and both virtual influencers have attracted endorsement deals from prominent brands. Nolan, however, questions their staying power. “It’s the imperfection,” she suggests “that ultimately creates connection.”

Virtual Influencers demonstrate the unreality of online presences. Although not real—mere figments of CGI—they have legitimate followings online with all the benefits that brings. Virtual influencers may rightly be seen as a mere gimmick, but use Tinder for awhile and you’ll notice that bots now live alongside people in our apps, and it takes at least a bit of effort to make sure you’re not mistaken for one of the bots. But as Nolan notes, virtual Influencers and bots more generally can’t compete in terms of imperfection and authenticity.

Crystal Abidin, an anthropologist and ethnographer of Internet culture, suggests in Internet Celebrity: Understanding Fame Online that “The Influencer ecology is thus moving from its peak of tasteful consumption formats toward an amateur aesthetic that feels less staged and thus more authentic.”1 This shift is what Abidin terms “performative authenticity.” In an age of manufactured content in which content from influencers begins to look all the same, some have begun to seek out a style that sheds aspirational perfection for relatable amateurism. But in the world of Influencers, imperfection is manufactured as easily as perfection.

⁕ ⁕ ⁕

Harvard Business Review provides another perspective, suggesting that social media platforms are best understood as gift economies.2 Gift economies are, as the name suggests, economies centered on gift giving—and they’re not merely hypothetical. The phenomenon was first observed in the fieldwork of anthropologists like Marcel Mauss. While in the field, Mauss observed a related phenomenon he called “potlatch,” in which a tribal society entered into a competitive sort of gift-giving. Status was won in this culture by out-giving one’s peers.

Potlatch is the model. In The Agony of Power, Jean Baudrillard claims that the West is engaged in a potlatch as we throw “indifference and abjection at others like a challenge: the challenge to defile themselves in return, to deny their values, to strip naked, confess, admit—to respond to a nihilism equal to our own.”3 Baudrillard describes a culture in an arm’s race of giving—in this case, giving oneself over to confession, to the compromise of values, and eventually to nihilism.

In the gift economy of Instagram, posts are shared not as part of a transaction, but rather for the status, clout, or recognition that comes from giving. As norms evolve on the platform and as the entrance of virtual Influencers highlights the issue of authenticity, social media users enter into an arms race, Instagram becomes a potlatch, and users must give more and more of themselves over to their virtual doubles if they want to imbue them with value in an increasingly competitive marketplace.

This is how users compete in the realm of the virtual: by committing more of their real lives to the maintenance of a virtual double. Whether it’s to compete or to escape, we’re all drawn into a virtual double of life inside our screens.