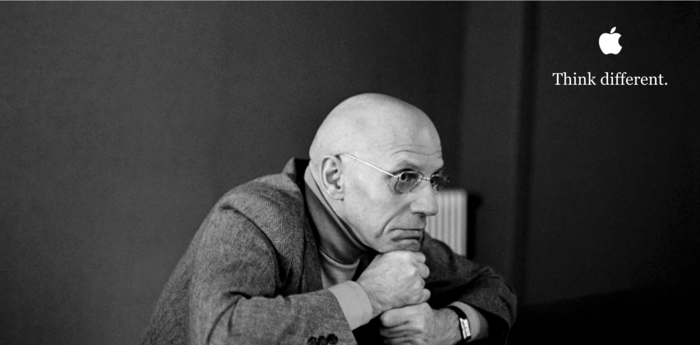

Here’s to the crazy ones

Apple’s most iconic ad featured a cast of famous misfits, rebels, and dreamers. I think Michel Foucault would’ve been a worthy addition. The campaign linked the company to a certain philosophy of the world—and this worldview, with its particular understanding of social change, has a lot in common with the work of Michel Foucault and the other founders of critical theory. A later interview with Steve Jobs, in which Steve says the following, makes the connection clear:

When you grow up you tend to get told that the world is the way it is and your life is just to live your life inside the world. Try not to bash into the walls too much. Try to have a nice family life, have fun, save a little money. That’s a very limited life. Life can be much broader once you discover one simple fact: Everything around you that you call life was made up by people that were no smarter than you. And you can change it, you can influence it… Once you learn that, you’ll never be the same again.1

French theorists and American technologists agree on an important point: “All that is solid melts into air.”2 What you call life was socially constructed and there’s no fixed center from which to assess it because the world is in flux.

The meme in Silicon Valley is that all these technology companies are “making the world a better place”. Steve Jobs may have sown the seeds of this mentality with the Think Different campaign, but there’s an important difference. “Here’s to the crazy ones” is not about social good, it’s about rewriting our social reality. The ad links rebels, artists, and computers with a vague sense of changing the world. It’s necessarily the social world being described—this is changing the world in the Bob Dylan sense, not the global warming sense. Additionally, this is change for its own sake: the ad calls for change, but there are no ideals nor higher values attached to it.

This is why technological disruption and critical theory make such a good match. Critical theory takes on the status quo, but by itself would erode the social order completely. Technology disrupts legacy institutions, but by itself has no telos. Critical theory gives technology license to tear down and technological disruption gives critique the tools it needs to rebuild. Although neither puts forward a constructive vision of the future, they are enough to engender a new sort of common ground.

This sort of common ground, however, will never be enough. In the new common ground there is no justice, no truth, and no legitimately-held power. There is only disruption and change for its own sake.

What is too often missing in pursuits of revolution is a vision of what’s worth preserving as vivid as one’s sense of what needs torn down. Everyone knows how Thomas Paine’s Common Sense was the spark that started the American Revolution, but fewer know that some of his fellow revolutionaries were unimpressed by the treatise. John Adams, for one, believed that Common Sense was simplistic. It sought only to tear down, but did none of the work to build up again. So Adams and others put in the work—drawing upon expertise in law and governance, and focusing on what we all have in common as humans—to imagine an alternative to the British Monarchy that preserved all the most important aspects of human flourishing, while doing away with the tyranny of our distant leaders.

Our technologists and theorists must now accept a similar responsibility. The frantic disruption of legacy institutions has lost its luster. The proponents of progress, whether social or technological, must stop simply trying to tear everything down—we need more people with a sense of what’s worth preserving, before too much more is lost.

Those who rage against the status quo and seek change for its own sake may, like Thomas Paine, be guilty of tearing down without a plan for rebuilding. In other cases, they may build disruptive technologies without the foresight to know whether they are unleashing a social good or ill. But they nonetheless knock us out of our complacency, and they make us all consider what it is that we stand for. So here’s to the crazy ones, and the sensible ones whom they will always startle into action.

-

Steve Jobs - One Last Thing (PBS, 2011). ↩

-

Marx & Engels, Manifesto of the Communist Party (1848). ↩